“Va pensiero", A Chorus for All Time

By Victor DeRenzi

In recent years, and especially during the COVID pandemic, the chorus of Hebrew slaves, “Va pensiero”, from Giuseppe Verdi’s opera Nabucco, written to a libretto by Temistocle Solera, has been performed often, live and on the internet. These performances have sometimes been planned, but they often seem to happen spontaneously, especially in Italy. During the last few months I have seen internet performances of “Va pensiero” from all over the world. It is easy to find over forty countries where it has been sung.

There was a time when most cities and towns had community choruses, a place where people of differing talents and life views could get together to share each other’s company and to express themselves through singing. Depending on where the chorus was located, its repertoire ranged from choral works by great composers to the folk music of the region. Over time many of these organizations have disappeared, and we have come to rely more and more on professionals to make music for us, either live or through recordings.

There are many beautiful musical works and several that could be considered greater than “Va pensiero”, so why has this one captured people’s hearts with such intensity? Like all great music, it functions on many levels - some of them easily accessible and some requiring a deeper look. Often with vocal music, that deeper look is as much about the text as it is about the music itself.

A chorus is a group of individuals who join to form a musically cohesive community; you are both yourself and part of something bigger than yourself. “Va pensiero” may be the perfect piece for people to come together and perform as a chorus. The melody is simple. It starts with everyone singing in unison, which gives confidence to those who are shy about singing. The experience of performing the same music helps them express their feelings while sharing their feelings with people around them. In the second section, it breaks into harmony, but you can still sing the melody and leave the harmony to those who have the ability to sing it. Finally, the music returns to a unison chorus, where everyone is united again with one voice.

Verdi was a composer who was affected by the words and how they express the human condition. He did not write about gods and goddesses but about people; people who share the same feelings no matter what society they belong to, and no matter their place within that society. Whether he speaks of Babylonians, Hebrews, kings, queens, great warriors, peasants, or courtesans, he makes us feel the joys and sufferings of everyone he represents on the stage.

In looking at this piece, it is important also to consider the words of the librettist, Solera, as well as Verdi’s music. People often sing unaware of the meaning of the text, sometimes even when it is their own language. It’s important to know the poet’s thoughts as well as the composer’s.

Here is the text in Italian followed by an English translation.

Va pensiero sull’ali dorate,

Va, ti posa sui clivi, sui colli

Ove olezzano tepide e molli

L’aure dolci del suolo natal!

Del Giordano le rive saluta,

Di Sïonne le torri atterrate…

Oh mia patria sì bella e perduta!

Oh membranza sì cara e fatal!

Arpa d’or dei fatidici vati

Perchè muta dal salice pendi?

Le memorie nel petto raccendi,

Ci favella del tempo che fu!

O simile di Solima ai fati

Traggi un suono di crudo lamento,

O t’ispiri il Signore un concento

Che ne infonda al patire virtù!

Go thought on wings of gold,

go rest on the slopes, on the hills

where the warm, soft breezes of our native land

spread their fragrant aroma.

Greet the banks of the Jordan,

The fallen towers of Zion…

Oh my homeland so beautiful and lost!

Oh remembrance so dear and fatal!

Golden harp of the prophetic bards,

Why do you hang silent from the willow?

Re-kindle memories in our breast.

Speak to us of times past!

Mindful of Jerusalem’s fates

Either give forth a sound of crude lamentation,

Or let the Lord inspire you to a harmony

Which instills in us the virtue to suffer.

The text is inspired by Psalm 137 of the Old Testament, and beautifully captures its overall feeling. The different Bible translations below have been chosen for their clarity.

“By the rivers of Babylon we sat and wept at the memory of Zion. On the poplars there we had hung up our harps. For there our jailers had asked us to sing them a song, our captors to make merry, ‘Sing us one of the songs of Zion.’ How could we sing a song of Yahweh on alien soil? If I forget you, Jerusalem, may my right hand wither! May my tongue remain stuck to my palate if I do not keep you in mind, if I do not count Jerusalem the greatest of my joys.”

Throughout this chorus there are references, biblical and otherwise, that would have been known to educated people during Verdi’s time.

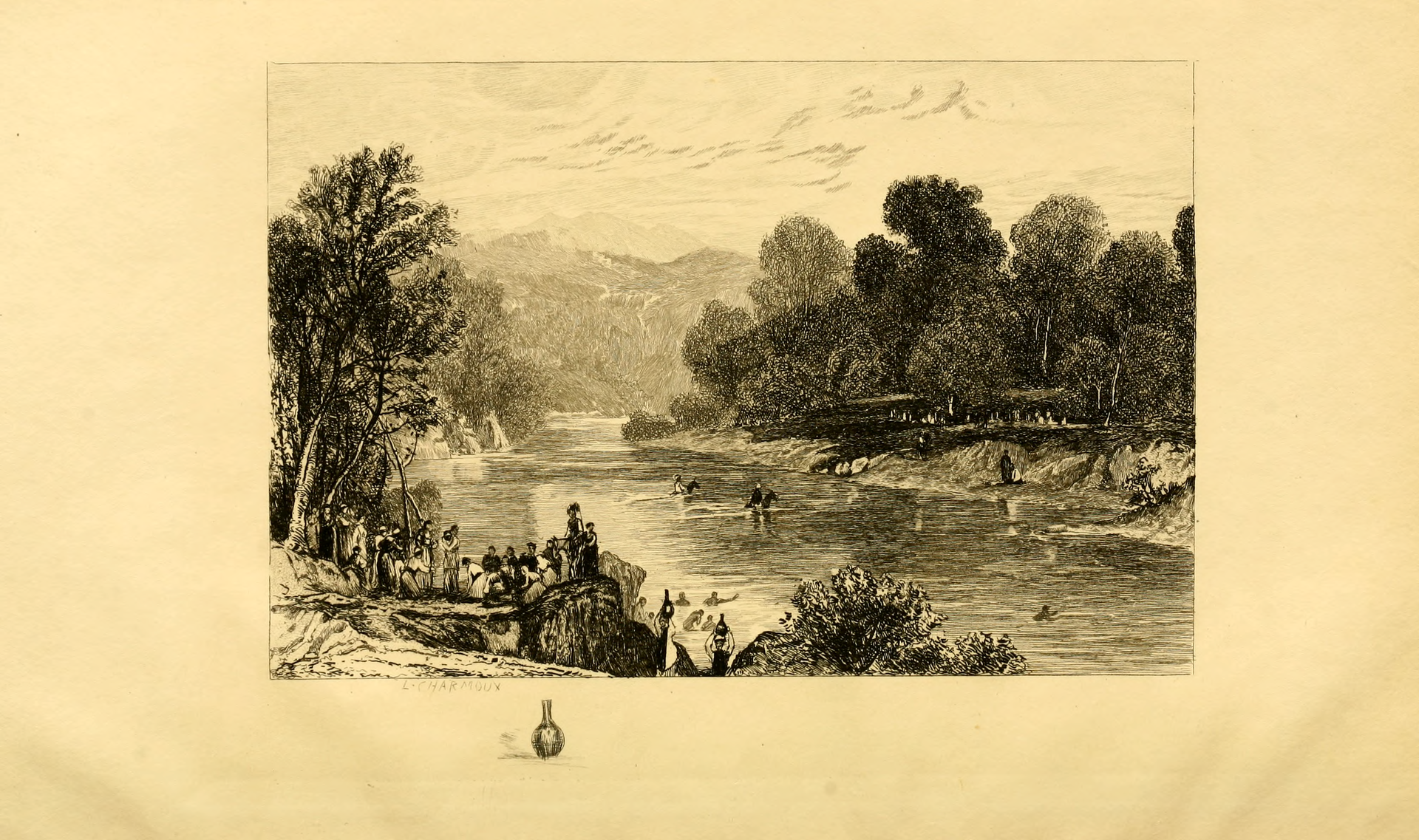

“Del Giordano le rive saluta” “Greet the banks of the Jordan”

The Jordan River was venerated by Jews, Christians and Muslims: crossing the Jordan marked the entry of the Jews into the Promised Land after the Exodus from Egypt, Jesus was baptized in the Jordan, and several of the Prophet Mohammed’s companions were buried on its banks. The Jordan kept its symbol into more recent times when it was used in Spirituals to signify the passing of the black slaves into freedom.

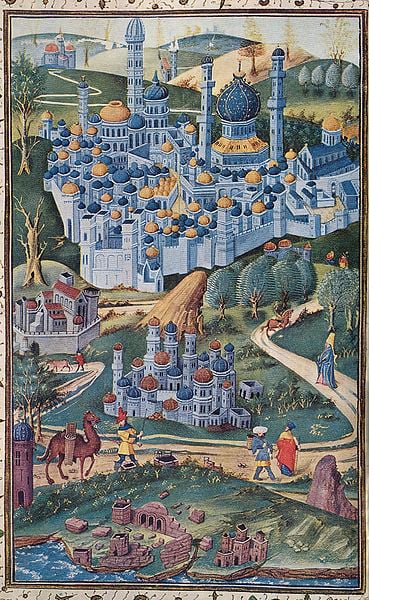

“Di Sïonne le torri atterrate” “The fallen towers of Zion”

The Bible refers to the towers of Zion in a way that signifies the life of the city and the wonder that will be there for future generations. Most of the city was destroyed by the Babylonians during the time Nabucco takes place.

“Let mount Zion rejoice, let the daughters of Judah be glad, because of thy judgments. Walk about Zion, go around her, count her towers, consider well her ramparts, view her citadels, that you may tell of them to the next generation.” Psalm 48

“Oh mia patria” “Oh my country”

There are three meanings to the word ‘o’ or ‘oh’ in Italian. 1. ‘O’ meaning ‘or’, as in ‘either/or’ found in the last lines of this poem. 2. ‘O’ as the vocative which is used to address someone or God directly, and 3. ‘oh’ that is used as an exclamation. In this line ‘Oh’ is not directed to the ‘patria’, ‘the homeland’, but it is an exclamation, as if in lamentation after seeing the fallen towers.

In Italian the word ‘patria’ has both a feminine and a masculine aspect; it is both motherland and fatherland, which is why I translate it as ‘homeland’ and avoid a gender. The word comes from the Latin word ‘patrius’, relating to father. ‘Father’ is obviously a masculine word, but in Italian that word is made feminine: ‘la patria’. Therefore, the homeland is both our father and mother.

“sì cara e fatal!” “so dear and fatal!”

‘Fatal’ does not mean fatal in the sense we use it in English, as something that will cause death, but rather it indicates something brought on by fate. Fate was thought of as God’s will; it was not haphazard coincidence.

“Perchè muta dal salice pendi” “Why do you hang silent from the willow?”

Our image of the willow goes immediately to the weeping willow. But, in the Bible it has various meanings. In Psalm 137, the willow symbolizes loss, along with hope for the future. But the willow maintains its life force. Ezekiel 17:5 speaks of the prophet taking a seedling and planting it like a willow tree, suggesting permanence and revival. The willow is also celebratory, as in Leviticus 23:40 which commands believers to take "willows of the brook" as a festival offering.

Yet Italian opera is not about thought or philosophizing. It is about action. When characters recall the past, they relive that moment rather than passively narrate it. Moments of prayer or remembrance on stage are also active; they are a way for a character to gather strength to move forward. The verbs, spoken and implied, keep “Va pensiero” active, just as Verdi’s accompaniment serves as a musical verb of action.

“Va pensiero” “Go thought”

The first word is a verb, ‘go’. The Hebrew slaves are speaking to thought, telling it to go where they cannot, to a better place, to home, to Jerusalem. I cannot go, but you can go for me.

“Va ti posa” “go rest”

I cannot rest, I am a slave, I am working for others, I am suffering, my people are suffering. You must rest for me in other lands.

There follows a series of nouns that involve our senses. We can see the “clivi” and “colli”, the slopes and the hills. We feel and smell the “aure dolci”, the soft, sweet breeze. The breeze is fragrant, and the word “molli” indicates that it is soft to the touch.

“Arpa d’or” “Golden harp”

The sense we are not experiencing is sound. We ask the golden harp why it is silent, and why even music failed us. Where has it gone? We see the harp hanging on the willow, but we do not hear it.

“Ci favella” “Speak to us”

At this point the text moves from the individual to the community, from ‘my country’ to ‘speak to us’. We cannot overcome this alone, we must unite.

These details lead me to some thoughts I feel are worth considering, ideas that can help us in times of need.

From the start of the chorus it is understood that though we are not in our country, we do have a community. We feel our suffering and we share the suffering of those around us. It is this communal bond that will save us. Our homeland is as much a people as a place. It is wherever we are, wherever we gather with others.

Though our country may be lost we still have our memories. We must hold on to them and pass them on. If we keep and share our memories, our history, we will still have hope. This has been the story of the Jews throughout history. It is one of the reasons the Jewish community still exists when other societies (such as the Babylonians) have vanished. We all have our own version of Jerusalem, a place, or a group of people that shares our innermost hopes and desires.

Humanity suffers continually. It is not enough to simply acknowledge and accept that suffering exists, we must also fight against it. Remembering will give us hope, and patience will lead us to action that will help us overcome suffering.

Composers like Verdi wanted their music to be performed in the language of the audience that was listening. Today in the theater we have the advantage of surtitles, but outside the opera house I wonder how much more we would gain from those performances if they were sung in the language of the people singing. Maybe Verdi would have liked those who sing it in Israel to sing in Hebrew, those in the United States and Britain in English and so on, thereby honoring the poet and finding the meaning in Solera’s words as much as in Verdi’s music. And, who knows, singing in our own language might help us become courageous so as to sing out with more feeling.