Stiffelio Background Notes

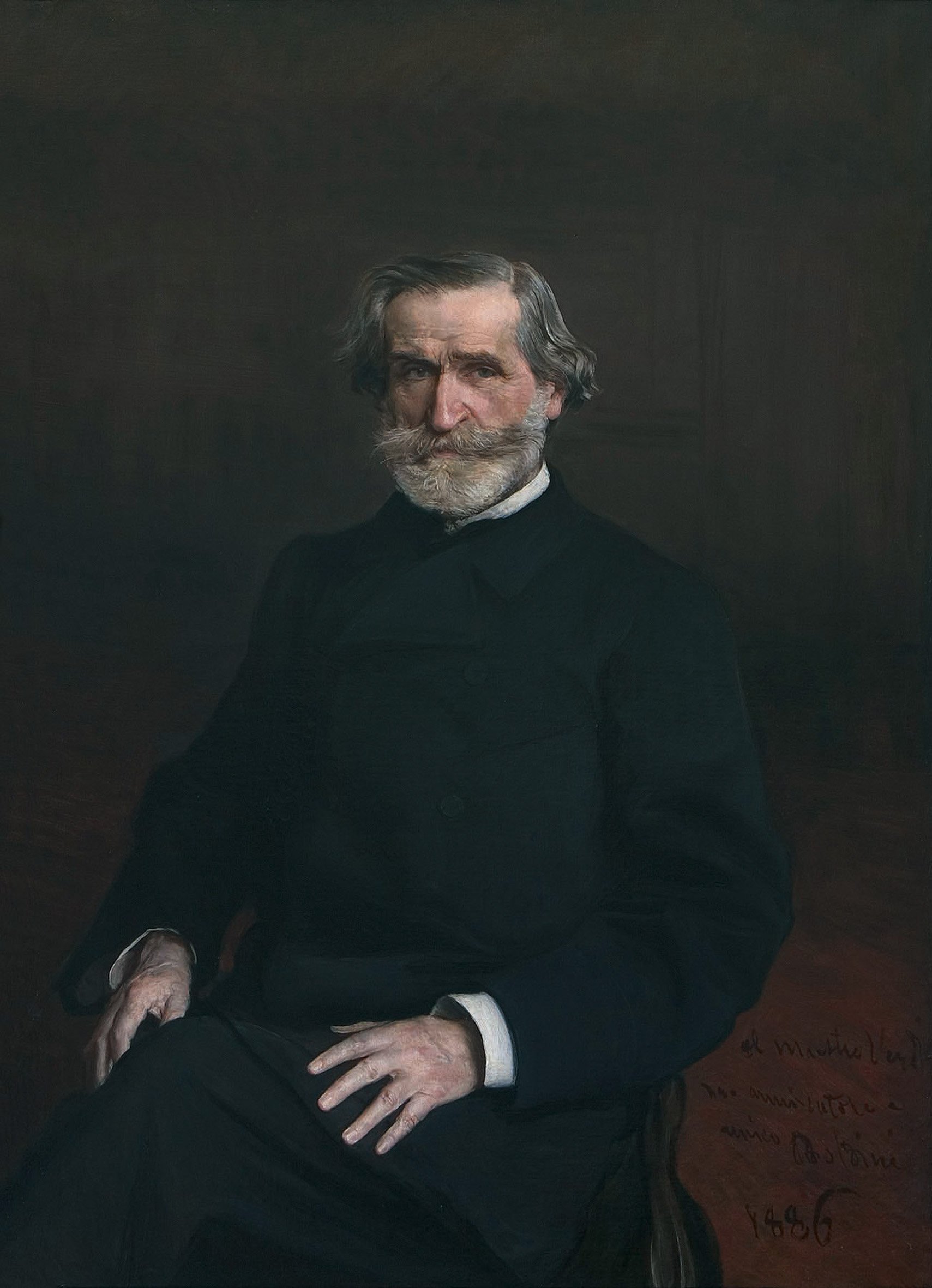

by Giovanni Boldini (1886)

In the early 1850’s, Verdi sought to stretch the conventions of Italian opera by staging two new works in modern dress: Stiffelio (1850) and La traviata (1853). With each, though the opera derived from a contemporary play, he failed: impresarios and audiences thought of opera as costume drama, and the period of Traviata soon was moved back to the early 1700s and was performed that way until about 1900.

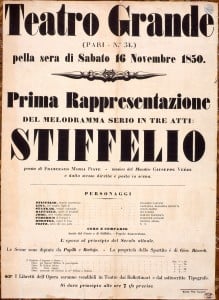

He had less luck with Stiffelio. At its premiere, in Trieste, most critics condemned the contemporary costumes, but far worse, only two days before opening night the work had to be revised to meet new regulations issued by the city’s Austrian government. These forbade onstage “any representation of sacred practices and church services of recognized religions” or of “sacred vestments,” and struck to the heart of the opera, which tells of Stiffelio, an itinerant Protestant preacher who on returning home discovers that his wife has had a brief affair with a young nobleman. Though a man of God, Stiffelio doubts: Can he forgive her? Can he practice what he preaches?

By the opera’s final scene, facing his congregation from the pulpit, he knows what God requires of him, and as a preacher and a man he publicly forgives her. Of Verdi’s twenty-three operas between Nabucco and Falstaff (not counting revisions), only Stiffelio offers a happy ending.

One might think that any Christian church or government would welcome such a drama. But no. At the premiere the final scene played without a cross onstage, or a pulpit, or anyone kneeling, and elsewhere impresarios set the opera’s period back to the 1400s and changed the story completely. Nowhere did Stiffelio play as Verdi wished. Frustrated, he withdrew it, suppressing performances, and seven years later used roughly forty percent of its music in another opera, Aroldo (1857), with Aroldo (Stiffelio) a fifteenth-century English crusader returning home. For a time Aroldo had a moderate success, but Stiffelio was silenced. Its music disappeared, and not until 1968, when perhaps eighty percent of it had been pieced together, was it performed again. Happily, by 1993 it was effectively restored in full.

Although the libretto often has tricks of concealment and coincidence, in the main it is excellent, posing three large themes wanting resolution: Stiffelio’s emotional conflict; the need of his wife, Lina, to convince him that despite her mistake she loves him; and the question of how her father Count Stankar, a retired military officer, will respond to the stain on family honor. Lina, in a powerful scene with Stiffelio, finally pierces his shell of indignation and vanity by signing the divorce papers that he offers and then demanding that as her preacher he hear her confession. That shakes him, and ultimately leads to forgiveness.

Stankar’s problem, conversely, is left partially unresolved. At first Stankar hopes to conceal the family’s shame and orders Lina to live a lie, never to tell Stiffelio of what has happened. When that proves impossible, he challenges the seducer to a duel, which Stiffelio, as a man of God, stops. At this point Stankar in a burst of anger reveals the seducer’s identity to Stiffelio. Later, he kills the seducer offstage and enters with his sword bloody. Those onstage are appalled and ask, “A murder? A duel?” He equivocally replies, “An expiation”. In the final scene he, like Lina, asks God for pardon. Performed now as Verdi conceived it, the opera has proved a sensitive music drama, a worthy predecessor to the three that followed: Rigoletto, Il trovatore, and La traviata.

GEORGE W. MARTIN

George W. Martin (1926-2023) was a Verdi specialist who has written several books on the subject including “Verdi: His Music, Life, and Times,” “Aspects of Verdi,” “Verdi in America” and “Verdi at the Golden Gate: Opera and San Francisco in the Gold Rush Years,” as well as many articles for various journals.