The Marriage of Figaro - Background oF the Opera

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) knew that success at the court opera house in Vienna was important to his well-being. Productions there had reverted to the Italian language, and Mozart, since composing the German opera with spoken dialogue Die Entführung aus dem Serail (The Abduction from the Seraglio) in 1782, had been seeking a suitable Italian libretto. He began setting to music L’oca del Cairo (The Goose of Cairo) and Lo sposo deluso (The Deluded Bridegroom) but abandoned both projects when he realized how slight their stories were. Mozart became acquainted with Lorenzo Da Ponte, an Italian adventurer of Jewish descent, and the composer suggested he write a libretto based on Beaumarchais’ La Folle journée, ou Le Mariage de Figaro (The Mad Day, or The Marriage of Figaro), the sequel to Le Barbier de Seville (The Barber of Seville). This earlier play had already been turned into operas by Friedrich Benda (1776) and Giovanni Paisiello (1782) and would attain operatic immortality in its setting by Gioachino Rossini (1816).

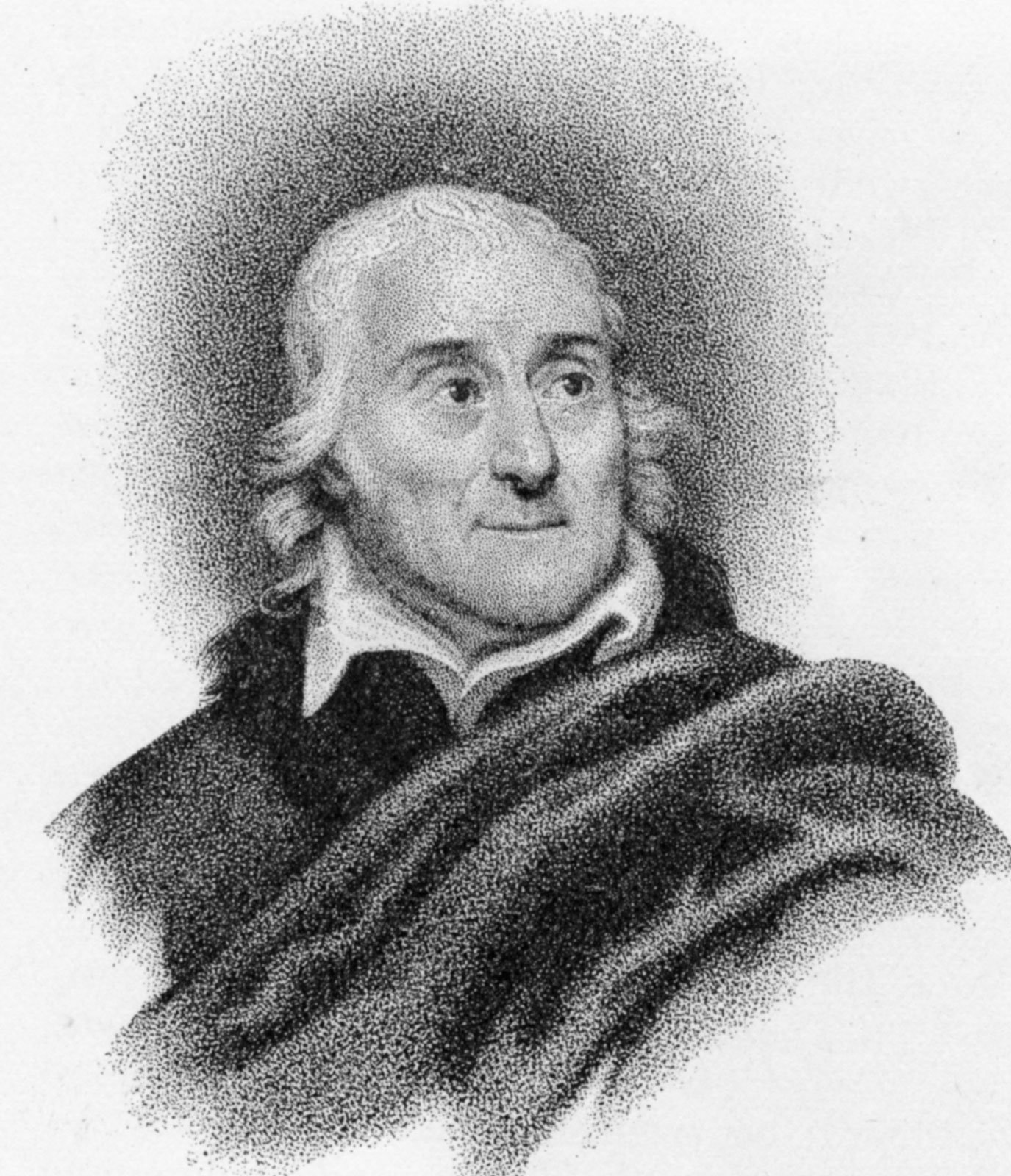

de Beaumarchais, author of

Le Marriage de Figaro,

by Marc Nattier (1755)

La Folle journée, ou Le Mariage de Figaro made a sensation in Europe. Louis XVI originally banned the play, believing it threatened the very foundations of social structure. However, powerful members of the aristocracy were able to persuade the king to let it be seen in 1784. It was a huge success. Twelve German translations of the play existed by the following year, and in Vienna, the theater troupe of Emmanuel Schikaneder (who later wrote the text for Mozart’s Die Zauberflöte) was forbidden to perform it. Da Ponte added buffo details to the original, especially to the characters of Basilio, Bartolo, and Marcellina, while concentrating the action and removing most of its overt political context. However, tensions between the classes and sexual conduct remain important themes of the libretto.

In adapting the play Le Mariage de Figaro for the opera house, Da Ponte wrote, “…I have not made a translation of that excellent comedy, but rather an imitation, or let us say an extract. For this I was compelled to reduce the sixteen original characters to eleven…and to omit in addition one whole act, many highly effective scenes and many witty lines… For these I have had to substitute ‘canzonette’, arias, choruses, and other thoughts and words susceptible of being set to music – things that can be handled with the help of poetry and never with prose…

Mozart did not compose the opera in order. He started with comedic sections and wrote the lyrical arias last. According to the New Grove Dictionary of Music, “Le nozze di Figaro may closely resemble other typical Italian opera buffa of the period, but the symphonic force of the music and its high degree of orchestral elaboration sets it apart. The finales of Act II and Act IV (each begins and ends in its own individual key) are long, multi-section ensembles with changes in meter, tonality, and orchestration, resolving existing tensions and creating new ones, always closely related to the action.”

Le nozze di Figaro was a success at its première; the singers encored many selections due to the audience’s favorable reaction. However, another opera with text by Da Ponte, Una cosa rara (A Rare Thing), eclipsed it. According to a contemporary, this work by composer Vincente Martin y Soler drove the Viennese to a frenzy.

The Sarasota Opera House is ideal in size for the performance of Mozart’s operas, and they are often a part of Sarasota’s repertoire. Recent productions include Don Giovanni in 2023 and Die Zauberflöte in 2019. The company last presented Le nozze di Figaro in 2015.

Greg Trupiano (1955-2020) joined Sarasota Opera in 1987 and was with the company until his death. He was also founder and artistic director of The Walt Whitman Project.